A leak that drips once per second can result in a loss of 405 gallons of oil in one year.

That's 7.4 standard barrels of oil per year lost to leaks; but the loss of all that oil is just one of the costs associated with leaking oil or hydraulic fluid.

Owners of hydraulic systems who detect leaks quickly or prevent them in the first place could find savings in equipment life, reliability, efficiency; not to mention avoiding costs associated with cleaning up spilled fluid along with many other associated costs.

Those costs add up quickly, but there are ways to combat the problem.

It is best to treat the source of the problem, but it's not always so simple. Leaks can have many causes: high temperatures, shock, improper maintenance and poor installation can all contribute to a dripping problem in a hydraulic system.

We have collected some of the top issues that contribute to leaks and how to address them, but one simple step that anyone can take is choosing a hydraulic oil with a distinctive color. It's simpler to train operators and frontline staff that a "green fluid leak" should be reported immediately because it is a high-importance hydraulic leak.

Here are some possible causes to consider and investigate either on your own or with the help of an expert once a leak has been identified:

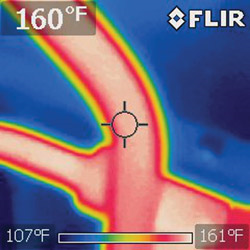

This relief-valve tank line should be at ambient temperature. In this example, the compensator setting was

increased, so the excess pump volume dumped over the relief valve when it was not used in the system, causing excess

heat in the hydraulic oil.

High Temperatures

There are many ways to measure the temperature of your system, but most hydraulic systems are designed to operate at 120°F (49°C), with a maximum temperature of 140°F (60°C). High oil temperatures can lead directly to leakage as well as other problems in the system. At high temperatures, O-rings tend to flatten out, become pitted and leak.The most common cause of heat in a hydraulic system is improper pressure settings. When a hydraulic problem occurs, usually every knob in the system is turned. The first adjustment made typically is on the pump's compensator. When the compensator's setting is reached and no volume is required in the system, the pump will de-stroke and deliver only enough oil to maintain the compensator setting. If this adjustment is set above the system's relief valve, the pump volume will return to the tank through the relief valve instead of being reduced to a flow rate of almost zero gallons per minute. This causes the temperature to rise above 140°F (60°C), resulting in O-ring failure as well as pump, motor and cylinder seal leakage. Those hydraulic oil leaks can lead to a variety of other costs both in the short and long term, so it's best to detect and manage those leaks quickly.

An Example from the Paper & Pulp Industry A mill that had heat and leakage problems on its debarker needed a solution. The unit was running at 205°F (96°C) and the system was leaking at the directional valve manifold, pump shaft seal and cylinder rod seal. When the pressures in the system were set properly, the temperature dropped to 130°F (54°C) within a few hours. Unfortunately, the damage to the O-rings and seals had already been done. The mill had to replace the pump, cylinder and valve O-rings.

This is just one example of how improper pressure settings can lead to temperature changes and ultimately, costly leaks.

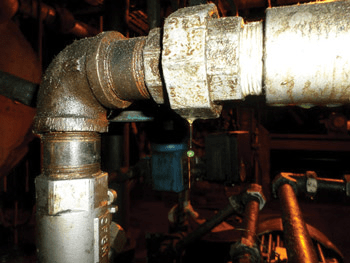

Pipe unions should never be used to connect pipes in a high-pressure line.

Hardware and Installation Errors

When using pipe to plumb a hydraulic system, schedule 80 and 160 pipe should be employed for pressure lines, while schedule 40 pipe should be utilized in the return and drain lines. Using schedule 40 pipe in the pressure line can result in leakage at the threads.A good hydraulic sealant should be used to seal pipe threads. Pipe dope and Teflon tape are not recommended simply because they are usually overapplied. Instead, apply sealant to the male fitting starting two threads from the end. When sealant is overapplied, it ends up in the hydraulic system, which causes leakage at the O-rings and cylinder rod seals as well as the hydraulic pump and motor seals.

When it's necessary to connect two pipes in a high-pressure line, always utilize socket weld flanges. Pipe unions should never be used as they are not designed to handle the shock and vibration in high-pressure lines.

The line from the pump to the valve manifold should not be piped rigid, particularly when closed center directional valves are used. Oil moves through a pressure line normally at 20 feet per second. The fluid speed may be higher or lower, depending on the pipe size and system pressure. When the solenoid on a closed center valve is de-energized, the oil flow from the pump is rapidly dead-headed at the valve. Since oil is relatively non-compressible, a pressure spike will occur. This spike can be two to three times the maximum operating pressure.

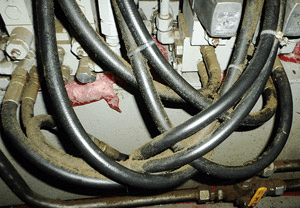

Improper clamping is one of the main causes of oil leaks.

Hose Leaks

A hose should be installed immediately downstream of the pump and just prior to entering the manifold. Hoses can help absorb a pressure spike. You should never pipe rigid into a cylinder except in the case of a suspended or vertical load. If a velocity fuse is mounted at the cylinder port, then a hose can be used. The velocity fuse will close if the hose ruptures, preventing a free-falling load condition.The length of the hose generally should not exceed 3 to 4 feet. The only exception is if the cylinder or motor is mounted on a movable carriage. During operation, the length of the hose can change by nearly 10 percent. Hoses that are too long end up rubbing against another hose, beam, catwalk or machine part. Even if the initial system installation used the proper length, the hose may incrementally increase in length over several years. This usually occurs because maintenance personnel cut the hose a little longer each time they replace it.

A hose that is too long will prematurely fail and cause a significant loss of oil from the reservoir. If hose rubbing cannot be prevented, a sleeve or protective cover should be installed. Many companies make sleeves that can be purchased by the reel. To prevent a considerable loss of oil from the reservoir, ensure the level switch is set just below the lowest level that the oil reaches when the cylinders are extended.

Another cause of leaks is improper clamping. Many times the wrong type of clamp is used. Beam and conduit clamps are not designed to prevent lines from moving when oil flow rapidly starts and stops in the line. Clamps made specifically for hydraulic pipes and tubing should be used and spaced approximately every 5 feet. A clamp should also be installed within 6 inches of where the pipe or tube terminates.

Hoses that are too long often rub against another hose or machine part resulting in leakage.

Common materials used in clamps include santoprene, polypropylene or other types of ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene. Clamps should be tightened periodically, as the bolts that connect each half can vibrate loose over a period of time. To prevent the clamp base from loosening, it should be welded (not bolted) to the beam.

Hydraulic pumps and motors often leak at the shaft seals. Shaft seals in single-direction pumps are usually rated at 10 psi. Shaft seals in hydraulic motors that have external drain lines are generally rated from 25 to 50 psi. The drain lines of pumps and motors should be run directly back to the tank and not in with the system return line. Filters and coolers are frequently located in return lines and will create some back pressure as the oil returns to the reservoir. In addition, high-flow surges in the return line can cause pressures to exceed the rating of the shaft seals.

Shock and Other Pressure Spikes

Hoses can absorb some of the shock that is generated in a hydraulic system. The other two devices normally used to reduce shock are relief valves and accumulators. The most common problem with relief valves is that the spring pressures are generally set too high. The system relief is usually located near the hydraulic pump and should be set 200 psi above the maximum operating pressure if a fixed displacement pump is employed. If using a relief valve with a pressure-compensating pump, a setting of 250 psi above the compensator setting is appropriate. When properly set, the relief spool will open for a moment, dumping the pressurized fluid back to the tank.Crossport relief valves are commonly found on the hydraulic motor drives of cranes, knucklebooms, and debarker and washer drives. These valves will open momentarily when the load starts moving and then decelerate the load when stopping. When oil is initially ported to drive the load, an initial pressure spike will occur. In the case of debarker and planer feedrolls, the spike is generated as the log or board is fed in. The crossport relief should be set to open when the pressure spike rises approximately 400 psi above what is required to drive the largest log or board. Improperly set crossports not only result in leakage at the system fittings but can also cause damage to the motor, machine and other system components.

Accumulators are excellent devices for absorbing shock in hydraulic systems. Generally, bladder or diaphragm types are used for absorbing shock. Threaded, in-line shock suppressors that are pre-charged with dry nitrogen have also become popular within the last few years.

When an accumulator is used to absorb shock, there are a few basic guidelines that should be followed. For instance, you should use a small accumulator (normally 1 gallon or smaller) and install it as close as possible to where the shock occurs. Also, be sure to pre-charge the accumulator with dry nitrogen approximately 100 psi below the pressure required to move the maximum load.

Remember, any time there is hydraulic oil leakage in a system, there's a reason for it. The entire system should be analyzed, and the problem for the leaks identified. Companies waste thousands of dollars each year because oil leaks have become accepted. Maintenance personnel must be trained on proper piping, clamping and hose installation procedures. Everyone in the plant should also be educated on the negative effects that random "knob turning" can have on machine operation, especially in hydraulic applications.